This page gives brief, visual reference for the most common commands in git. Once you know a bit about how git works, this site may solidify your understanding.

This page is a copy of a web page1) that I found recently describing GIT in a visual way. It really helped me to understand the operations of GIT so I decided that I wanted make a copy of the website here for my future reference. The contents of the article is subject to the original authors copyright and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License.

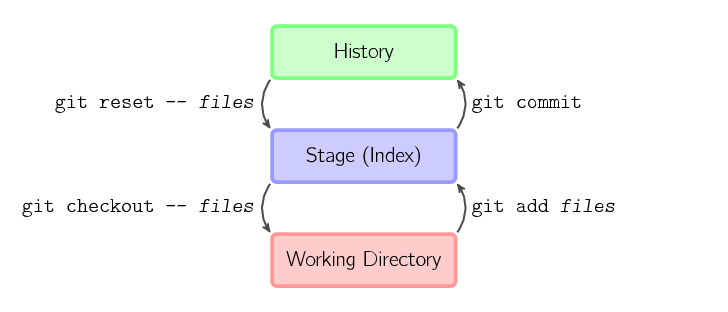

The four commands above copy files between the working directory, the stage (also called the index), and the history (in the form of commits).

The four commands above copy files between the working directory, the stage (also called the index), and the history (in the form of commits).

git add files copies files (at their current state) to the stage.git commit saves a snapshot of the stage as a commit.git reset – files unstages files; that is, it copies files from the latest commit to the stage. Use this command to “undo” a git add files. You can also git reset to unstage everything.git checkout – files copies files from the stage to the working directory. Use this to throw away local changes.

You can use git reset -p, git checkout -p, or git add -p instead of (or in addition to) specifying particular files to interactively choose which hunks copy.

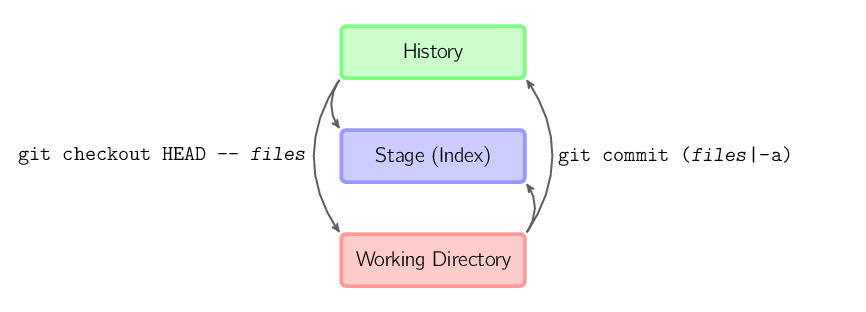

It is also possible to jump over the stage and check out files directly from the history or commit files without staging first.

git commit -a is equivalent to running git add on all filenames that existed in the latest commit, and then running git commit.git commit files creates a new commit containing the contents of the latest commit, plus a snapshot of files taken from the working directory. Additionally, files are copied to the stage.git checkout HEAD – files copies files from the latest commit to both the stage and the working directory.

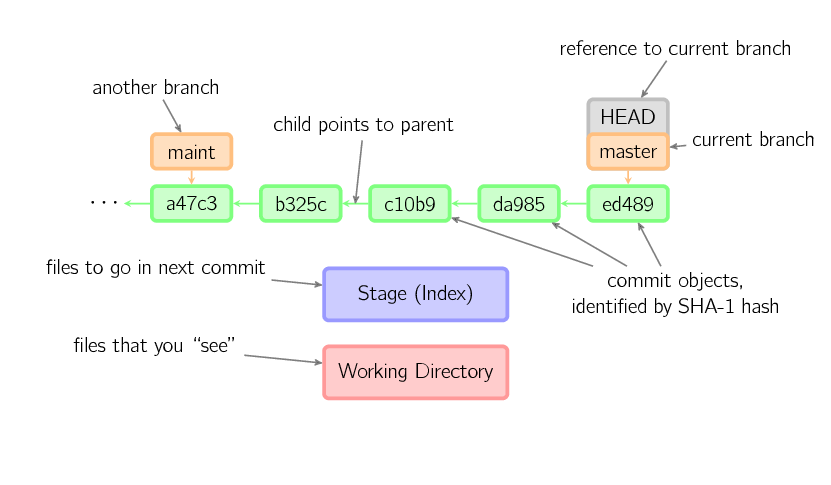

In the rest of this document, we will use graphs of the following form.

Commits are shown in green as 5-character IDs, and they point to their parents. Branches are shown in orange, and they point to particular commits. The current branch is identified by the special reference

Commits are shown in green as 5-character IDs, and they point to their parents. Branches are shown in orange, and they point to particular commits. The current branch is identified by the special reference HEAD, which is “attached” to that branch. In this image, the five latest commits are shown, with ed489 being the most recent. master (the current branch) points to this commit, while maint (another branch) points to an ancestor of master's commit.

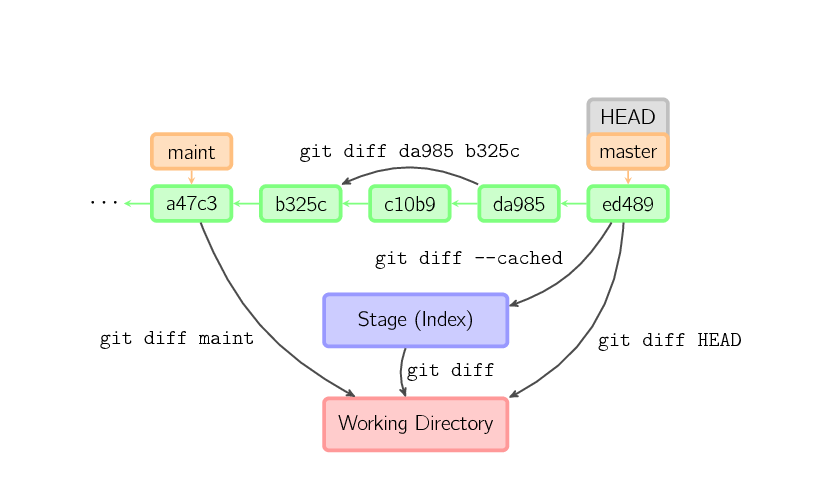

There are various ways to look at differences between commits. Below are some common examples. Any of these commands can optionally take extra filename arguments that limit the differences to the named files.

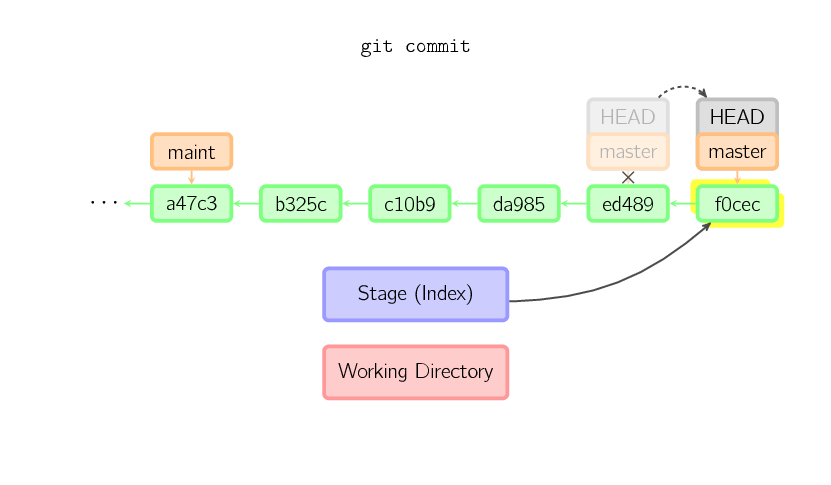

When you commit, git creates a new commit object using the files from the stage and sets the parent to the current commit. It then points the current branch to this new commit. In the image below, the current branch is master. Before the command was run, master pointed to ed489. Afterward, a new commit, f0cec, was created, with parent ed489, and then master was moved to the new commit.

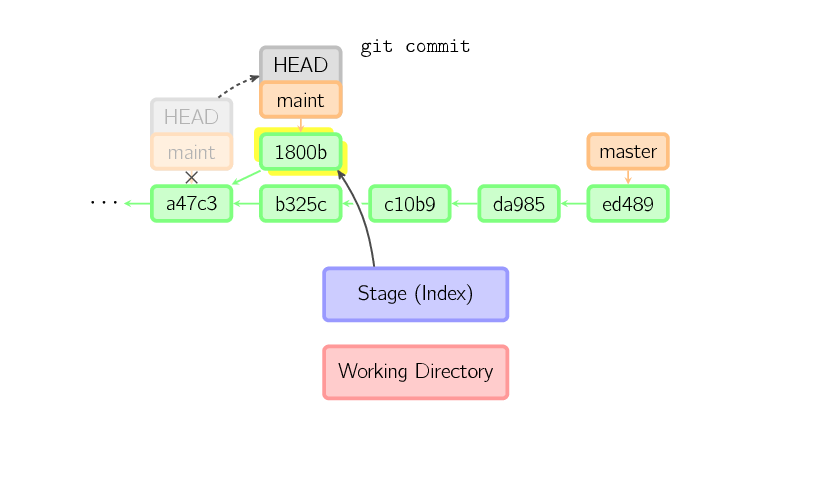

This same process happens even when the current branch is an ancestor of another. Below, a commit occurs on branch

This same process happens even when the current branch is an ancestor of another. Below, a commit occurs on branch maint, which was an ancestor of master, resulting in 1800b. Afterward, maint is no longer an ancestor of master. To join the two histories, a merge (or rebase) will be necessary.

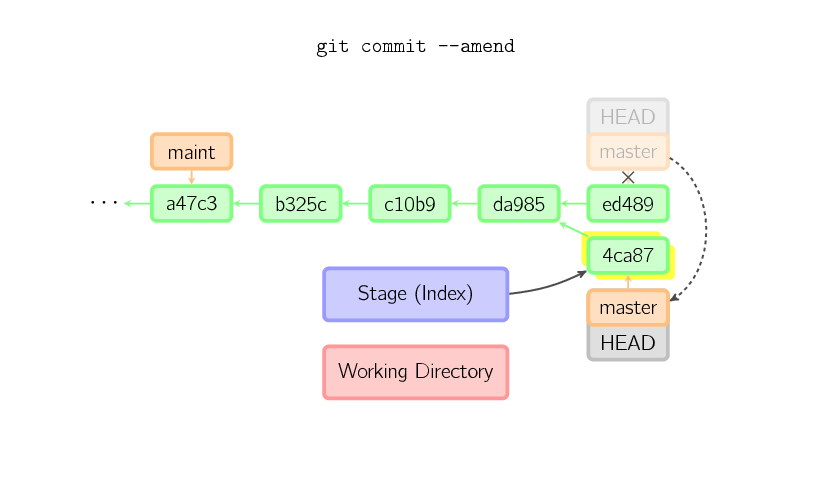

Sometimes a mistake is made in a commit, but this is easy to correct with

Sometimes a mistake is made in a commit, but this is easy to correct with git commit –amend. When you use this command, git creates a new commit with the same parent as the current commit. (The old commit will be discarded if nothing else references it.)

A fourth case is committing with a detached HEAD, as explained later.

A fourth case is committing with a detached HEAD, as explained later.

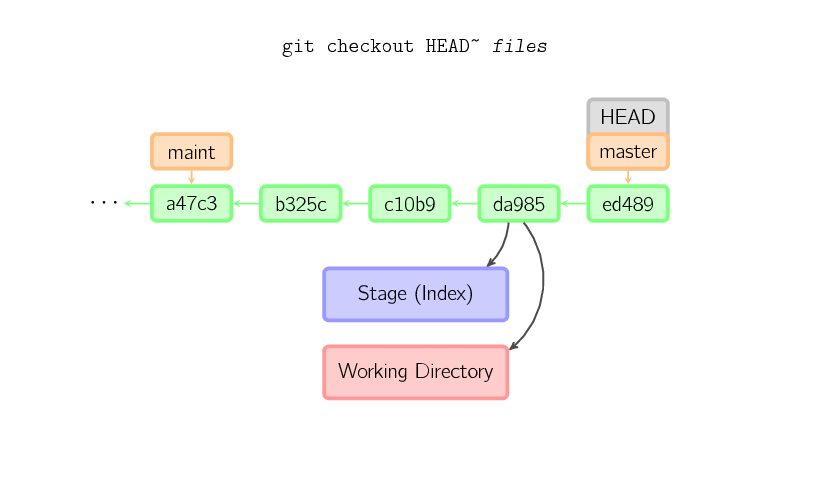

The checkout command is used to copy files from the history (or stage) to the working directory, and to optionally switch branches.

When a filename (and/or -p) is given, git copies those files from the given commit to the stage and the working directory. For example, git checkout HEAD~ foo.c copies the file foo.c from the commit called HEAD~ (the parent of the current commit) to the working directory, and also stages it. (If no commit name is given, files are copied from the stage.) Note that the current branch is not changed.

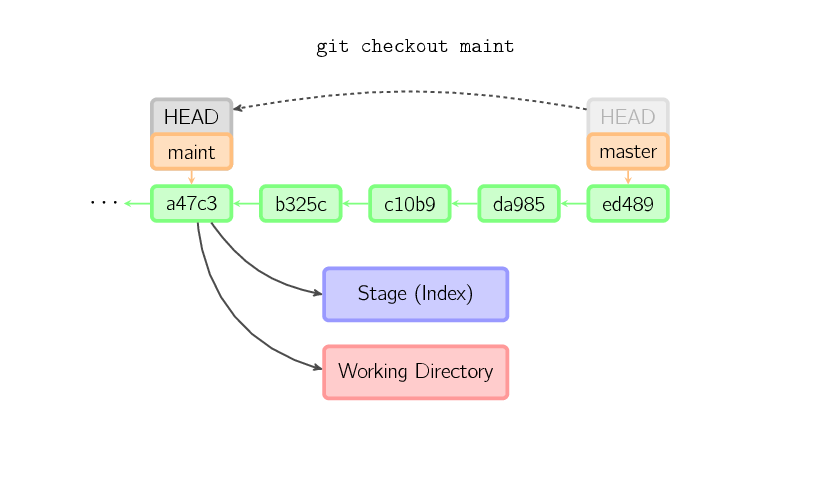

When a filename is not given but the reference is a (local) branch,

When a filename is not given but the reference is a (local) branch, HEAD is moved to that branch (that is, we “switch to” that branch), and then the stage and working directory are set to match the contents of that commit. Any file that exists in the new commit (a47c3 below) is copied; any file that exists in the old commit (ed489) but not in the new one is deleted; and any file that exists in neither is ignored.

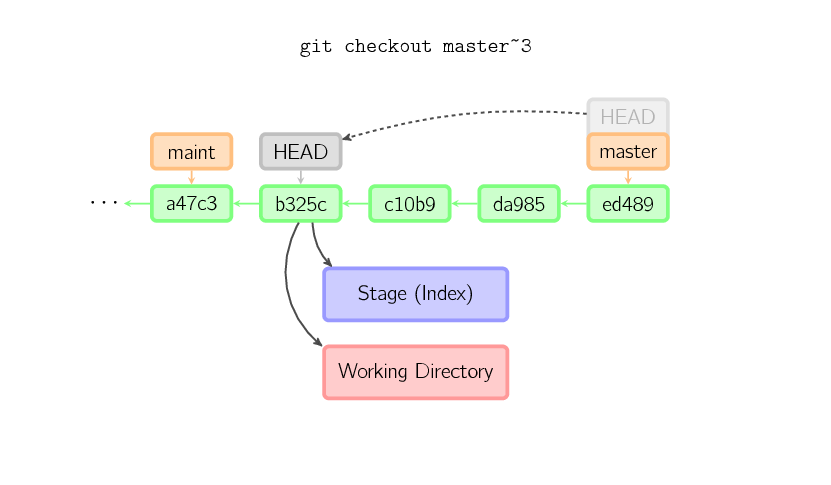

When a filename is not given and the reference is not a (local) branch — say, it is a tag, a remote branch, a SHA-1 ID, or something like

When a filename is not given and the reference is not a (local) branch — say, it is a tag, a remote branch, a SHA-1 ID, or something like master~3 — we get an anonymous branch, called a detached HEAD. This is useful for jumping around the history. Say you want to compile version 1.6.6.1 of git. You can git checkout v1.6.6.1 (which is a tag, not a branch), compile, install, and then switch back to another branch, say git checkout master. However, committing works slightly differently with a detached HEAD; this is covered below.

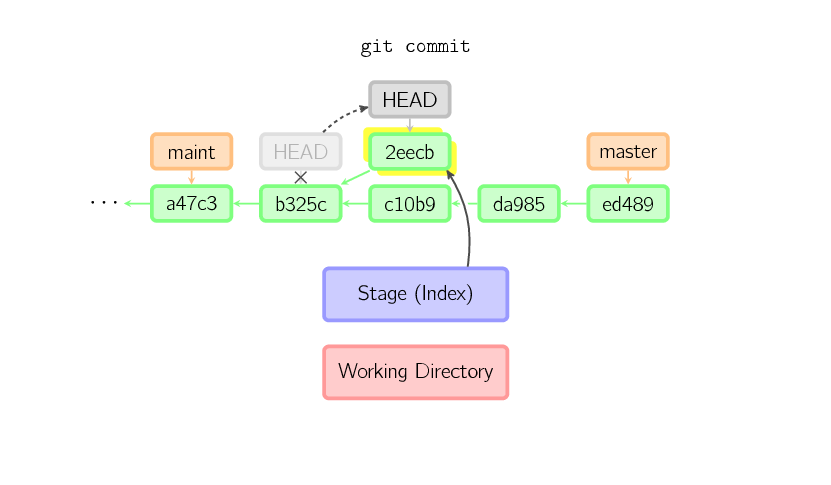

When HEAD is detached, commits work like normal, except no named branch gets updated. (You can think of this as an anonymous branch.)

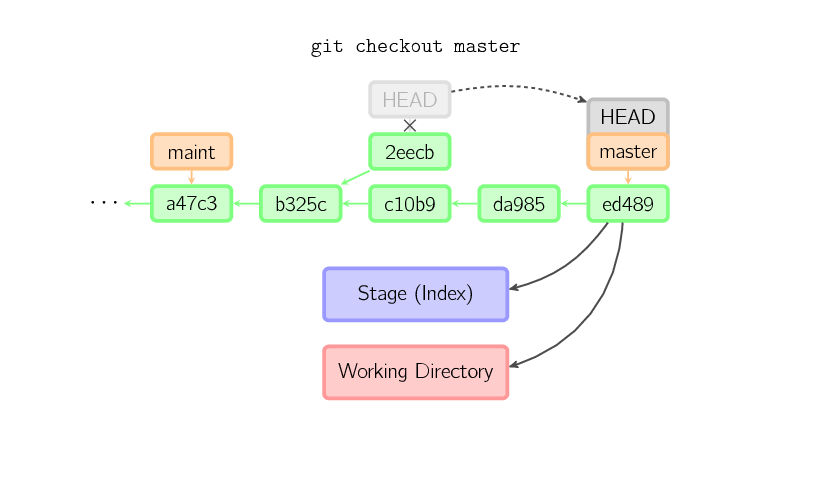

Once you check out something else, say

Once you check out something else, say master, the commit is (presumably) no longer referenced by anything else, and gets lost. Note that after the command, there is nothing referencing 2eecb.

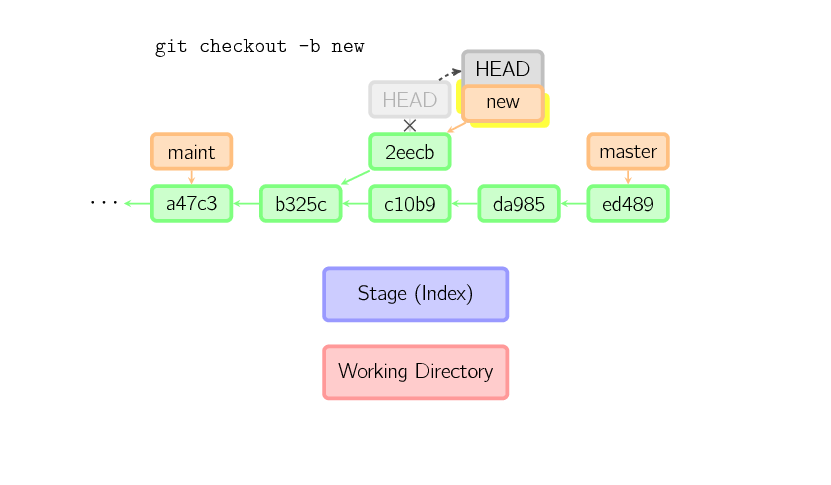

If, on the other hand, you want to save this state, you can create a new named branch using git checkout -b name.

If, on the other hand, you want to save this state, you can create a new named branch using git checkout -b name.

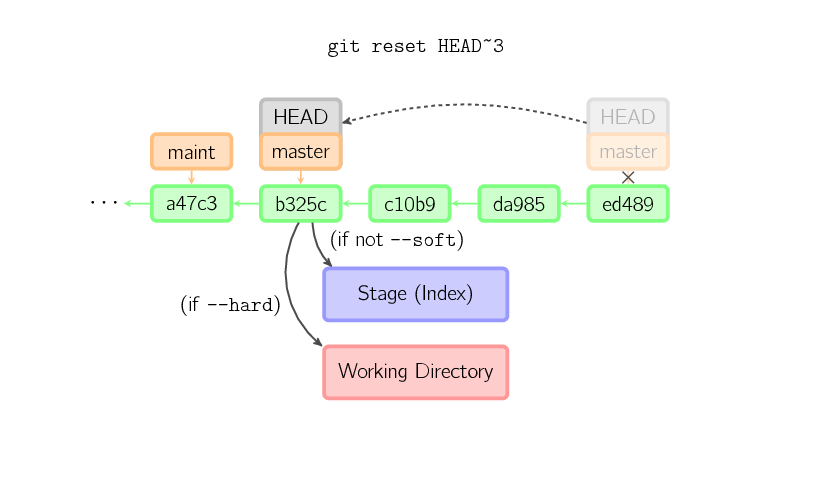

The reset command moves the current branch to another position, and optionally updates the stage and the working directory. It also is used to copy files from the history to the stage without touching the working directory.

If a commit is given with no file names, the current branch is moved to that commit, and then the stage is updated to match this commit. If –hard is given, the working directory is also updated. If –soft is given, neither is updated.

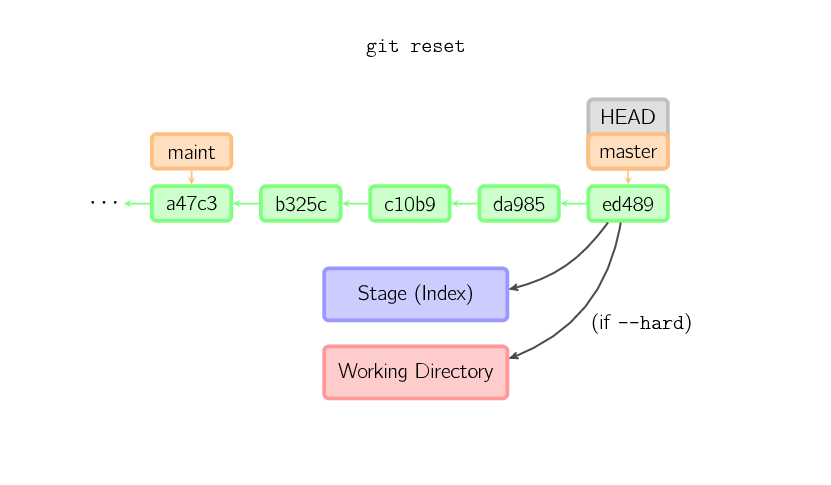

If a commit is not given, it defaults to

If a commit is not given, it defaults to HEAD. In this case, the branch is not moved, but the stage (and optionally the working directory, if –hard is given) are reset to the contents of the last commit.

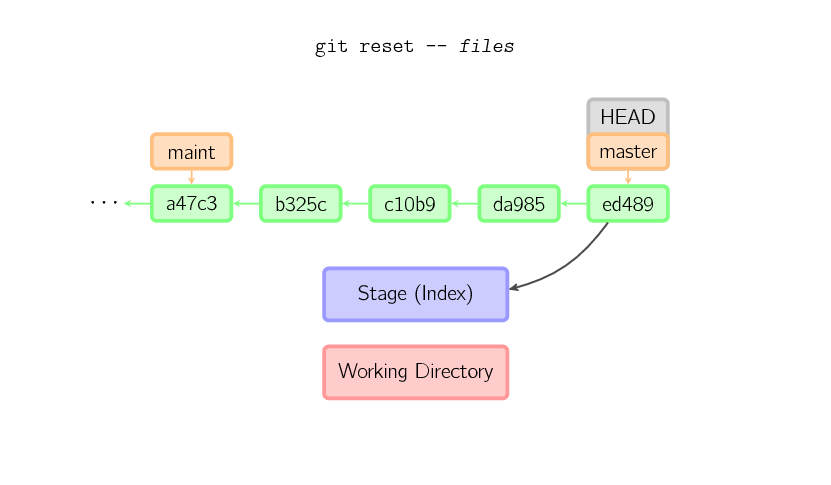

If a file name (and/or -p) is given, then the command works similarly to checkout with a file name, except only the stage (and not the working directory) is updated. (You may also specify the commit from which to take files, rather than

If a file name (and/or -p) is given, then the command works similarly to checkout with a file name, except only the stage (and not the working directory) is updated. (You may also specify the commit from which to take files, rather than HEAD.)

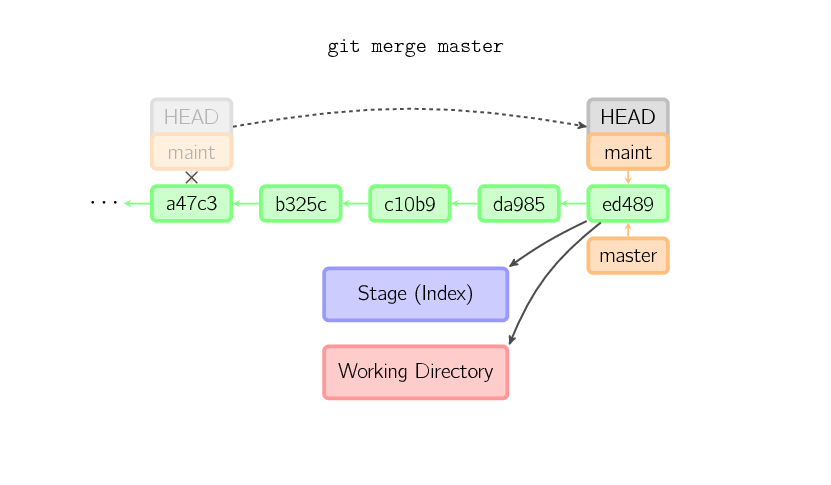

A merge creates a new commit that incorporates changes from other commits. Before merging, the stage must match the current commit. The trivial case is if the other commit is an ancestor of the current commit, in which case nothing is done. The next most simple is if the current commit is an ancestor of the other commit. This results in a fast-forward merge. The reference is simply moved, and then the new commit is checked out.

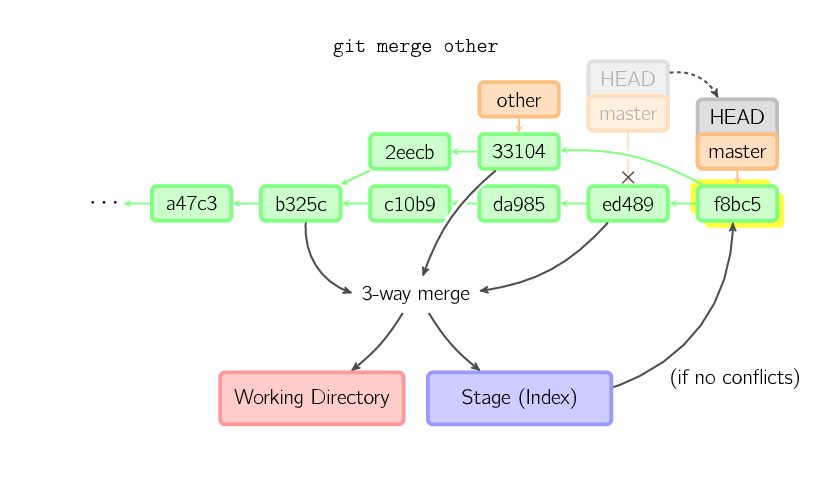

Otherwise, a “real” merge must occur. You can choose other strategies, but the default is to perform a “recursive” merge, which basically takes the current commit (

Otherwise, a “real” merge must occur. You can choose other strategies, but the default is to perform a “recursive” merge, which basically takes the current commit (ed489 below), the other commit (33104), and their common ancestor (b325c), and performs a three-way merge. The result is saved to the working directory and the stage, and then a commit occurs, with an extra parent (33104) for the new commit.

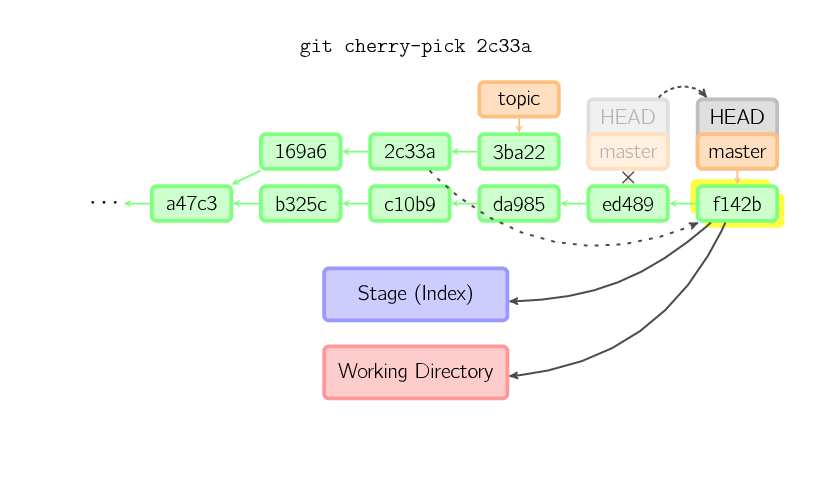

The cherry-pick command “copies” a commit, creating a new commit on the current branch with the same message and patch as another commit.

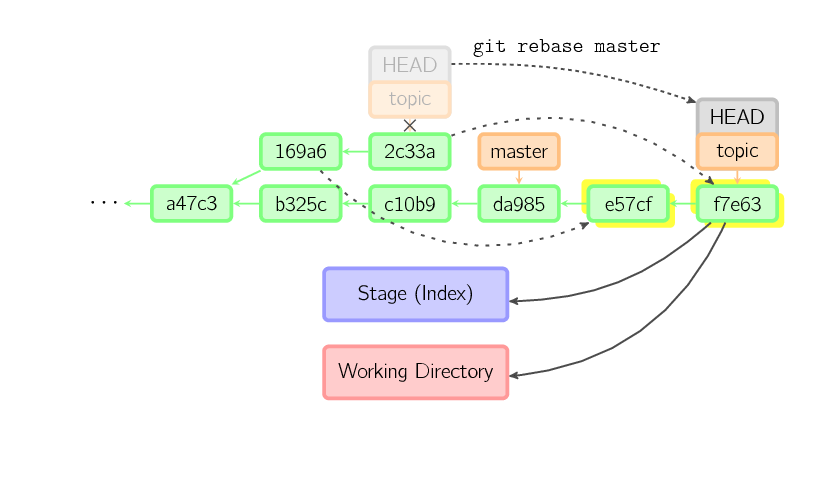

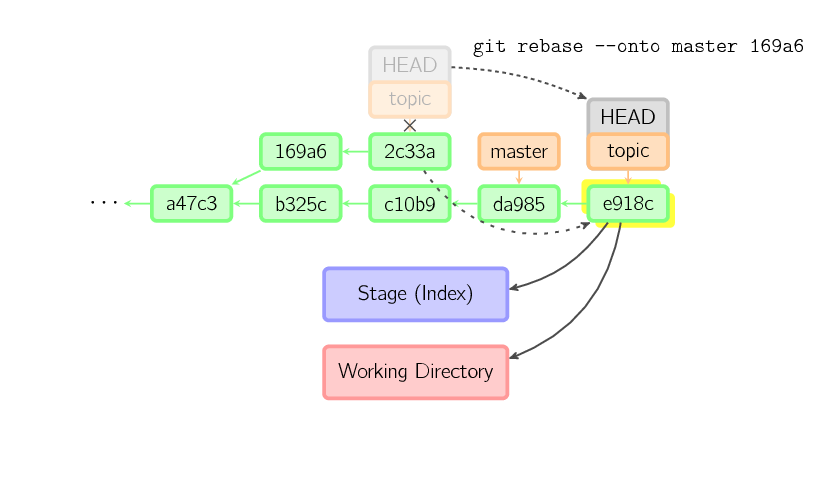

A rebase is an alternative to a merge for combining multiple branches. Whereas a merge creates a single commit with two parents, leaving a non-linear history, a rebase replays the commits from the current branch onto another, leaving a linear history. In essence, this is an automated way of performing several cherry-picks in a row.

The above command takes all the commits that exist in

The above command takes all the commits that exist in topic but not in master (namely 169a6 and 2c33a), replays them onto master, and then moves the branch head to the new tip. Note that the old commits will be garbage collected if they are no longer referenced.

To limit how far back to go, use the –onto option. The following command replays onto master the most recent commits on the current branch since 169a6 (exclusive), namely 2c33a.

There is also

There is also git rebase –interactive, which allows one to do more complicated things than simply replaying commits, namely dropping, reordering, modifying, and squashing commits. There is no obvious picture to draw for this; see git-rebase(1) for more details.

The contents of files are not actually stored in the index (.git/index) or in commit objects. Rather, each file is stored in the object database (.git/objects) as a blob, identified by its SHA-1 hash. The index file lists the file names along with the identifier of the associated blob, as well as some other data. For commits, there is an additional data type, a tree, also identified by its hash. Trees correspond to directories in the working directory, and contain a list of trees and blobs corresponding to each file name within that directory. Each commit stores the identifier of its top-level tree, which in turn contains all of the blobs and other trees associated with that commit.

If you make a commit using a detached HEAD, the last commit really is referenced by something: the reflog for HEAD. However, this will expire after a while, so the commit will eventually be garbage collected, similar to commits discarded with git commit –amend or git rebase.